Something about Super Chicken looked familiar.

The style and format. The cheesy one-liners delivered in a strange, staccato pace. The big-bellied characters with skinny arms and legs.

It was like that other cartoon with the Moose and Squirrel, somehow from the same world, but distant at the same time.

I was in someone else’s house while my father visited the owner. Left on my own in this strange living room, I was drawn to the television and whatever was playing. I was always drawn to TV in places like this.

This strange heroic chicken was talking to me.

This was Super Chicken.

Years later I learned it was created by Jay Ward and Bill Scott, the same crew behind Rocky and Bullwinkle, Dudley Do-Right, and more. All those cartoons were released just a few years before I was born, but they aired on random days and times on one of Atlanta’s several UHF channels that easily caught my childhood attention.

The first formative years of my life as a 1970’s kid from Atlanta were highlighted by the existence of Channel 17, which was just about the best channel possible. Don’t argue with me on that.

And things on Channel 17 were always changing.

One day I’d tune in expecting one program only to discover some new oddball import like Battle of the Planets, where the character’s lips never matched what was being said. It was a cartoon, of course, so the lips and voices rarely matched anyway, but with Battle of the Planets, it was like they didn’t even try.

It didn’t matter, though. Shows came and went so rapidly that I was always in the throes of some new unknown piece of entertainment.

They aired the best reruns in syndication. For all I knew at the time, every episode was brand new.

Batman was all new.

Brady Bunch was all new.

Super Chicken was all new.

Gomer Pyle and Addams Family and The Munsters and Lost in Space and The Flintstones were all new.

Everything was new, at least to me.

I don’t know if those shows actually aired on Channel 17 or one of the other competing UHF stations at the time, but it was all the same to me. They were fantastic. They took me out of my head and somewhere safe where I somehow mattered, where stories were somehow real, where I could step into the Batcave or the S.S. Minnow and belong, where I was there in Eddie’s room with his crazy telephone while Bill Bixby was off on some courtship, and it wasn’t strange for me to be there.

Later, I’d hold imaginary conversations with these fictional characters. I’d endlessly talk with Casper the Friendly Ghost. I’d re-enact scenes from Batman over and over.

I was Batman.

I cannot adequately explain how devastating it was to come home from school, retreat to the basement, and flip on Channel 17 fully expecting to lose myself for the next three hours, only to find an Atlanta Braves game in progress.

Devastating.

Originally nothing more than a local Atlanta UHF station, Channel 17 was one of the first broadcast properties gobbled up by media magnate Ted Turner. He purchased it in 1970 and renamed it WTCG, which stood for “Watch This Channel Grow.” Sometime around 1976-1977, he changed it again to WTBS for “Turner Broadcast System.”

But every kid growing up in 1970s Atlanta just knew it as Channel 17.

This, of course, later became the first cable “Superstation” that most people know simply as TBS, broadcasting everyone’s favorite reruns all across the country.

There were other local competitors on other UHF frequencies — Channel 36 and Channel 46 — but they were soon absconded and shut down as Ted Turner grew his formidable empire. Fortunately, this didn’t happen until after I first moved away from Atlanta (I’d return two other times in my life, disappointed that the UHF landscape had been mostly obliterated in my absence).

UHF was a safe haven, even though I didn’t know I needed one.

In the cul-de-sac behind our house, there were two brothers, both slightly older than me.

One day, playing in the dried-out culvert on the right side of their house, talking about a Tarzan movie we’d all seen recently on Channel 17, those two brothers lured me through the doors next to the culvert that led into their dark, musty, unfinished basement.

There, they threatened me and tricked me into taking off my pants.

“If you don’t, we’ll tell your mom that you were doing something.”

Something.

This part is hazy for me. I don’t remember the details of the threat itself, only that they made me lay down on the concrete floor and they both took off their own pants.

And if I didn’t do as they told, something terrible would happen.

I was four-years-old. Maybe five.

The details of what happened next aren’t worth writing.

You don’t want to know the details.

Needless to say, I spent more time by myself after that, and I avoided the cul-de-sac.

On November 7, 1976, the day after my sixth birthday, the same year Channel 17 had the best shows in Atlanta, I suffered another abuse — non-sexual this time — at the hands of someone I trusted and loved.

Again, details aren’t necessary, only that I was silently instructed to never complain, to never displease.

Don’t assert myself.

Acquiesce at all times.

The unspoken threat was this: or else.

Or else, what? I didn’t know, nor did I want to find out.

What was being formulated in my young mind, though, was that I was not safe. And even if I thought I was safe, that could change without warning at any moment. And if I wasn’t good, things would get worse.

Being small and wiry, the best safeguard I found was in further withdrawal from the world around me and into the safe technological haven where all problems were tidily wrapped up in 30-minute sitcoms and animated adventures.

Easy, simple, convenient solutions. It was all so appealing because the things that had already happened to me so early in life never happened on television.

What happened on the television comforted me with what was happening in real life.

When my family moved to Columbus, Ohio at the beginning of 1979, we landed on a one-street private drive with seven homes. Five of these homes had kids within a few years of age of me.

Upon our arrival, I was flabbergasted at the complete absence of any UHF channels except PBS. It was a travesty.

Even worse than a single afternoon derailed by baseball, in Columbus I was completely without a decent channel to entertain me at all.

Sure, at 4 PM every afternoon one of the local network affiliates would air a single half-hour Scooby-Doo episode and a handful of Looney Tunes, but that was it. On Sunday mornings before Mass, another station aired old black and white Blondie and Dagwood movies.

But where were Gilligan’s Island and The Brady Bunch? Where were the back-to-back episodes of Batman? What about Gomer Pyle and Carol Burnett and Sanford and Son?

Where was Channel 17, home of Saturday night wrestling and movie after movie after movie (except for when one of those cursed Braves games took over)?

What else would I watch on the family TV, the monstrous piece of furniture entrapped in an overly ornate wooden cabinet? Donahue? Please.

Gone were the days of rapidly turning the UHF dial — ratta tatta tatta tatta tatta tatta tatta — from one channel to the next in between commercials, constantly on the search for a wonderful new distraction.

Within the first year in Columbus, the high school kid next door, a dark-haired bully who laughed at everyone, came up from behind me and pulled down my gym shorts and underwear while a group of kids — including girls — were in his garage. I yanked up my pants as quickly as I could, but I had already been exposed.

Another kid from two doors down gave me a frozen lemonade popsicle. He didn’t eat one. When I finished, he told me he’d peed in it and made it just for me. I never found out if was lying.

A couple of years later that same teen from next door - even though he was several years older than me — would be the first person to ever hit me so hard that the wind would be knocked out of me. I can still remember where I stood in our front yard, next to our Buckeye tree, hunched over and choking for air as that teen sat on his bicycle seat and laughed.

Long after we moved away, that same jerk attended my brother’s wedding in 1990. When everyone else was throwing rice in the air as the newlyweds departed, one of my many childhood bullies walked up and dumped all his rice down the back of my shirt.

A few years into our stay in Ohio, during the summer before seventh grade, my parents got a new television and let me occasionally take their antiquated TV to my room downstairs. One day, completely by accident, I stumbled upon a technological miracle.

On a boring weekend afternoon, I haphazardly clicked through the UHF channels I’d already searched through for years, staring at static as I remembered my earlier, more joyful, channel surfing in Georgia. As I made my way through the 30s and into the 40s, the static suddenly jumped on the television.

Back then, older television sets had rings around the UHF and VHF channels that fine-tuned stations in conjunction with rabbit ear antennas. I continued to twist the rings to the right, twisting, twisting, twisting. With each turn, the wiggling pattern of lines and static evened out and acted less erratic.

Then I heard a voice: distinctly audible speaking. With another couple of turns, I suddenly had a crystal clear image.

What was this?

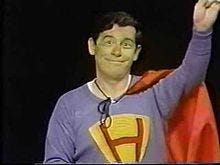

A guy appeared on my screen dressed like a dopey version of Superman. Blue suit, red cape, a big red “H” in the middle of a yellow triangle on his chest. He had a painted red nose like a clown, and black hair parted to the side with a very slight spit curl, just like Superman sported in the comics.

He introduced himself as Superhost before presenting a Three Stooges short, some weird sketch or another, and a few other gags before launching into an obscure black and white monster movie.

Again: “What is this?”

My heart was singing.

After Superhost ended his afternoon hosting gig, there were cartoons and Batman reruns (Batman! I hadn’t seen Batman in years!).

Somehow, magically, I was tuned into WUAB channel 43 in Shaker Heights, just outside Cleveland almost 150 miles away.

I didn’t know how this was possible, and I didn’t care.

Without a TV Guide for the Cleveland area, I never knew what was about to come on channel 43. Every half hour felt like a jackpot, except for one thing:

Like Channel 17, more frequently than I would have liked, Channel 43 interrupted their regularly scheduled programming to air Cleveland Indians baseball games. Alas.

I soon discovered late-night The Twilight Zone reruns. Channel 43 aired episodes at 11 and midnight, airing some other program in between. In Columbus, the local PBS affiliate aired a single episode of Twilight Zone at 11:30 PM.

So each night I’d twist twist twist to tune in to Rod Serling in Cleveland, then twist twist twist to tune the Columbus channel back into focus, then twist twist twist to go back to Cleveland, usually falling asleep in between Burgess Meredith or William Shatner overacting in the midst of some awesome twisted tale that occurred just beyond the signpost up ahead in another dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind.

The summer I discovered Channel 43 was like a respite before more trying times began again.

Once school started up that year, three of my seventh-grade classmates were the second to pummel the breath out of me after one of them spit in my ear and chased me into the boy’s bathroom where they took turns to sucker-punch my gut.

We moved again at the end of the year (again to a place where there were no UHF channels) and no sooner had eighth grade begun when a burly and always dirty-looking kid pushed and tripped me at the same time, breaking both of my wrists. I rejoiced when he was held back to repeat the grade while I moved on to high school.

By November of my sophomore year, I’d moved three more times, so often I was already in my fourth high school in less than two years.

My parents and I were back in Ohio again, this time in Cincinnati. And again, there was no UHF channel, but one of the local major network affiliates aired a one-hour block of M*A*S*H* every afternoon, which provided somewhat of an escape between 4 and 5 PM.

The next summer I got a job and found a couple of people to hang out with from time to time. But no real connections. I had a few acquaintances but spent most of my time alone.

At the beginning of my junior year in high school, I offered some girls in my neighborhood a ride to and from school. They were pretty girls, all popular, with a wide group of friends I’d observed from the back of the classroom the year before.

We had a few classes together that year, and it felt like I was slowly becoming part of something more hopeful.

On a rainy Friday afternoon two weeks into the school year, as we round a very tight bend in the road on the way home, my car hydroplaned on new asphalt and plowed head-on into a tree.

My car was totaled.

The two girls in the back weren’t wearing seatbelts, but were relatively unscathed. The front bench seat, however, came off the railings. Even though I was wearing my seat belt, my face was slammed against the steering wheel.

Out of the four of us in the car, I was the only one so severely injured that I was hauled away in an ambulance. My nose was split open and shattered.

That night, a rerun of Steven Spielberg’s Amazing Stories anthology aired. It was an episode I’d seen only once before, but it was my favorite: Family Dog, created by Brad Bird, who would go on to helm future favorites of mine, The Iron Giant and The Incredibles.

I had to turn it off ten minutes in because my face hurt so much every time I laughed.

I awoke in the middle of that night after the accident with the distinct ghostlike feeling of my seatbelt strapped across my chest. I could still feel it, hours later. My skin was tender and my chest hurt from where the seatbelt restrained me.

Two weeks later, I had reconstructive surgery that left me bandaged and bruised, with dark raccoon-like circles around my eyes that didn’t recede for months.

The day of my surgery, September 28, 1987, was the day Cheers began in syndication, at least in Cincinnati. I recuperated in my parent’s bed so that my mother wouldn’t have to go up and down the stairs all day. Again, I couldn’t watch the show without it physically hurting my face.

That night, the very first episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered. I was never much of a Star Trek fan, but I’d been looking forward to this new approach to syndicated television that was independent of UHF channels. Unfortunately, I was on so much pain medication that I was asleep within minutes of the show starting. I never bothered to go back to watch it again.

The girls I had given a ride stopped talking to me. Their other friends ignored me then, as well.

There has been this strange pattern, a roadmap of entertainment, that has tracked me throughout my life, over thousands of miles of moves and relocations.

If you were to name a movie or TV show, I could most likely tell you the year it came out (plus or minus about twelve months). The recall of these release dates is often associated with some other event with details I don’t think I can adequately convey.

For most of my life, I’ve pretended many of the abuses I’ve endured were as inconsequential as the shows I binged. The memories are often dreamlike and hazy, therefore they must not be important. And, like most television programs, they certainly don’t have any significance in my life today.

But that’s not entirely true.

A few years ago, I found myself in a new situation of workplace bullying. It’s also sometimes referred to as workplace mobbing, where multiple people are involved in teaming up against others.

I was surprised to learn this was actually a thing as it sounds almost made up. I was even more surprised that even in my forties, I had stumbled into the snares of bullies once again.

It was a terribly discombobulating experience of gaslighting and deceit that ended up being the final straw in my lifetime of unexpected and unprovoked aggressions.

What happened at this job, this workplace mobbing, was the incident needed to finally crack the veneer of protection I’d tried so hard to hold in place.

All at once, the years of never feeling safe came gushing out and I collapsed under the pressure.

I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and went on disability. Doctors pumped me full of pharmaceuticals, but pharmaceuticals are useless if core traumas aren’t addressed.

The cul-de-sac.

The silencing abuse.

The bully next door.

The bathroom beating.

The car accident.

Core traumas cannot be addressed if all we do is seek solace and retreat, whether in the form of self-medication, alcohol, food, or UHF TV.

A little over a year ago, the pressure and pain of so many unaddressed wounds brought everything to a halt.

I’d attempted therapy several times since around the age of seventeen, but not much helped because most of the time the solution offered was in the form of a pill.

I entered the confessional one Saturday morning in June 2021. I don’t remember exactly what I said or what I confessed, but the priest behind the screen honed in on my psyche like a laser beam.

“Are you in therapy of any kind?” he asked.

“No,” I told him. “I was for a while, after being diagnosed with PTSD, but not now.”

“Okay,” he said. “I recommend two things. Come to confession every week, at least for the next few months. And look into getting back into therapy.”

There was a comfort in his directness. I’d tried so many things, and sought out so many other ways to find solace, but his two-step approach was plain and simple and somehow lovely.

The next Saturday I returned, and again and again in the weeks to follow.

I also sought out a therapist and landed on one who has led me through the far-reaching landscape of memories that have brought me to this place in time where healing from all these wounds seems more possible than ever before or ever imagined.

This past year I’ve revisited so many of the traumas that were unfairly beset upon a much, much younger version of myself.

So many traumas were given to this four-year-old, then six-year-old, then twelve-year-old, and on and on, and each time that child — at whatever age — sought refuge in fictions that only masked an unfortunate reality.

The question I continually ask my therapist at the end of an intense session of revisiting my past is, “So what do I do with that?”

Now that I see these patterns: now what?

What do any of us do with the wounds that fester over the years?

There is healing to be had, and both good and bad memories can play parts in that difficult and often time-consuming process.

Many of these memories I long tried to tune out, but their signals were still being broadcast like phantom radio waves bouncing endlessly through space.

They were broadcast with scrambled messages of you don’t belong, you’re damaged, you’re bad, you’ll always fail.

In many ways, this last year has been like that summer in Columbus with the old rundown television. I’m twist twist twisting the rings around the channels, dialing in old memories and bringing them into clearer focus.

It’s amazing that even the worst of the memories are starting to turn into incredible blessings the more I twist twist twist and tune in those memories of events that I thought once scarred me forever beyond recognition.

In one session, my therapist led me on a journey back into the basement of those two brothers. He had me imagine that moment that first sent me into seclusion and seeking distractions from the pain of the world.

There I was in the basement, on the cold concrete floor, the brothers hovering over me.

I saw the far recesses of the basement as nothing more than blackness. All light in the room was being swallowed up and was almost gone.

Why was this happening?

How could I have been left alone? How could no one know these brothers would do this to me?

And at that moment, in my imagination, looking back nearly fifty years, a single pinprick of light appeared out of nothing.

The light grew and glowed and began to swallow up the blackest corners of that basement, even covering those two brothers and whatever pain might have once been inflicted upon them that would cause them to lash out at someone else even more helpless than they were.

The light was everywhere, and in the middle of it, I saw Mary, the Mother of God.

“Keep focusing on that,” my therapist told me.

Mary, cloaked in brilliantly white robes, stretched out her arms and wrapped me entirely in her mantle.

Together, we floated through the basement doors and were now outside, near the culvert where just minutes before I was still safe and unscarred.

The Blessed Mother sealed up the doors. The lone window to the basement, under which those boys had betrayed my trust, vanished from existence.

Still in her arms, I floated with Mary to the very center of the cul-de-sac. The entire world was filled with light.

Sitting on the couch in my therapist’s office, I could see this image more clearly than any image I ever brought into focus on any UHF channel in any city at any time in my life.

Mary lifted my chin to look upward, to the brightness of the sky, to the image — coming into greater focus even today — of what my life still could be, and what surprises may appear as I continue to twist twist twist my eyes into focus.

That's a brilliant piece of writing. A hopeful ending (Mary is always giving us those - even in her darkest apparitions) Our world is missing those. Thank you for sharing this.

I am sorry all this happened to you Greg. Thankful you are now at a place where you can face it. What a beautiful ending to see how Our Blessed Mother has brought healing into your life. This is probably the most moving and powerful thing you’ve ever written. For yourself, bringing Hope ing healing for yourself and letting others know, they are not alone and not worthless. God has a purpose and will bring healing, if we allow him. Interesting to see how priests in a confessional have been major factors at least twice in your life. Also your “story” masterfully written and told here. I’m not much of a writer but really appreciate others who can tell or craft a story. Well done sir. Praying for you and your family.