One Anxiety Attack at a Time

It’s quite an exciting week as we’ve had a significant influx of new readers over the last few days. I’m so very glad you’re here. Thanks for reading!

Name Endorphins

Reminder - if you find a typo in my serialized novel, Eighty-Sixed, I’ll give you a “Typo Finder” editor credit in the published edition when the book eventually goes to print.

The same goes for all paid and founding member subscribers!

Thanks to this week’s typo finders Elizabeth, Evelyn, Lisa, Rose, and others who helped shine the blaring editorial spotlight on a handful of sneaky mistakes that barged their way into a recent chapter of Eighty-Sixed. They’ve all been fixed thanks to you!

And thanks to Jon, Joan, and Julie for recently becoming paid subscribers. Y’all are awesome. (Apparently, if your name starts with a J, you were obligated to become a paid subscriber this week.)

Losing my Mind with Worry

“I try not to worry about the future — so I take each day just one anxiety attack at a time.”

— Tom Wilson

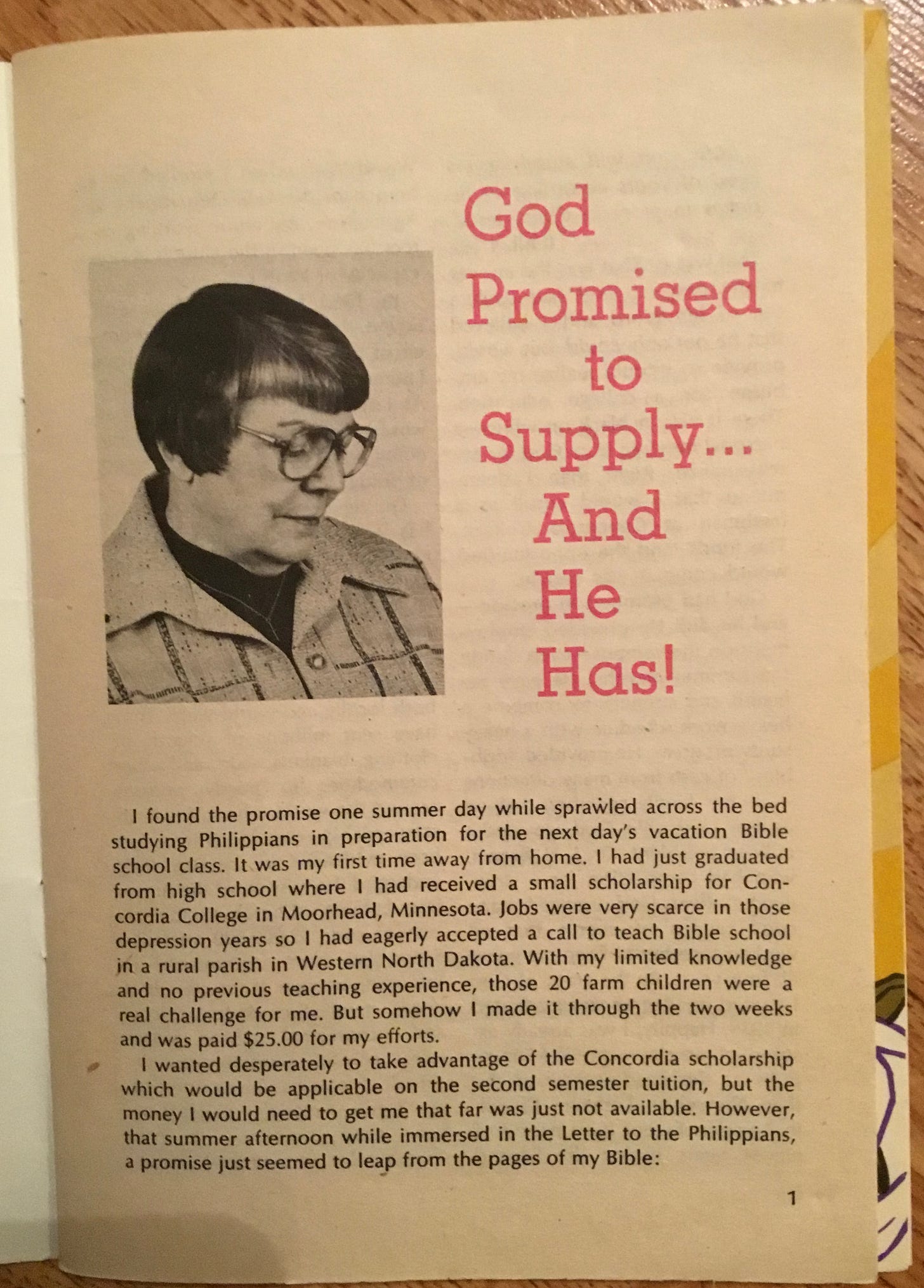

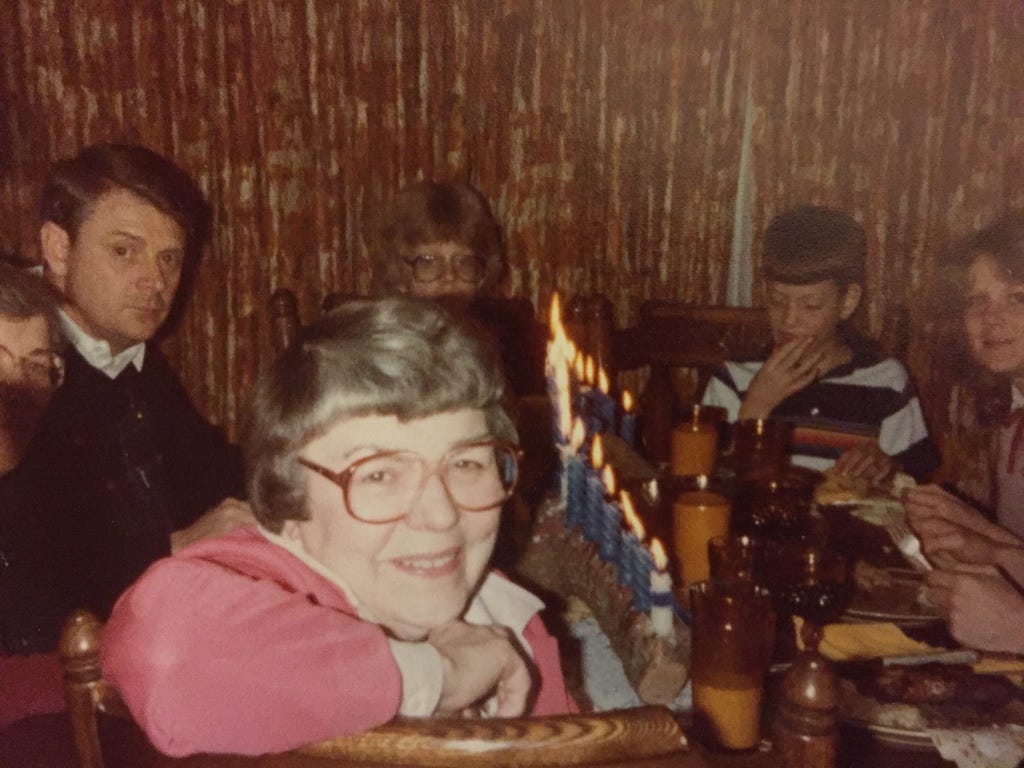

Lily Gyldenvand was a round little woman with a permanent smile, squinty eyes and big glasses, an affinity for pink polyester leisure suits, and the same short bobbed haircut that she wore year after year after year. A wordsmith, she crafted books and articles and letters and, as editor of a Christian women’s magazine, pieced them together before her words made their way into thousands of homes each month.

Her influence increased her reach, but never her vanity, as she became a sought-after presenter, traveling constantly to speaking engagements in between regular retreats into the basement of her small home on the outskirts of St. Paul, Minnesota. There, she painted and knitted and crafted through multiple other creative endeavors. She was always making something out of nothing.

The sister of my grandmother on my mother’s side, Great Aunt Lil was the first true artist in my life. She could do anything, it seemed, and was interested in everything. Quick to laugh and tell a story, she was a great woman and the first inspiration in my own early artistic pursuits. She traveled almost annually to visit our family wherever we moved to over the years, and was the only one to volunteer to take me to see Superman 2 in the movie theater when no one else wanted to go — even though she promptly fell asleep shortly after the opening credits.

On top of all of this, Aunt Lil is solely responsible for introducing me to the wonders of peanut butter and bacon on toast. Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.

In line with her habit of constantly writing, Aunt Lil prolifically wrote letters and postcards, keeping us always up to date on her nonstop activities.

When I was in elementary school, Aunt Lil sent our family a postcard one summer day with a simple greeting.

“Hope all is well for your clan,” she wrote. “Excited to see you when you come to visit this summer. Weather has been nice lately. Miss you all.”

It was a typical Aunt Lil postcard, written in her practiced cursive script, neat and orderly, the obvious product of years of practice.

The next day another postcard arrived with an eerily similar greeting.

“Hope all is well for your clan. Excited to see you when you come to visit this summer. Weather has been nice lately. Miss you all.”

Nearly every day for the next several weeks, the same postcard greeting arrived in our mailbox.

Over the following years, as I progressed through high school and finally into college, Aunt Lil’s brilliant mind slowly devolved into near incomprehension of daily events as Alzheimer’s slipped in and ravaged her from within. When I last saw her while traveling through Minnesota in September of 1988, my parents and I stopped to have lunch with her. Several times during our meal she’d turn to me, surprised to see someone sitting next to her, and ask, “And who are you?”

“I’m Greg, Aunt Lil,” I answered her.

“My goodness!” she exclaimed. “How’d you get so tall?”

Minutes later she’d forgotten the conversation entirely, and once again was completely surprised to see me sitting in the seat next to her.

“And who are you?” she’d ask again.

A short time after, Aunt Lil slipped into unconsciousness before passing away.

Nearly twenty years later, my wife and I were running two nonprofit organizations full-time. Two years prior I had left a career in the IT industry, where I had worked for over ten years, in order to devote my time to producing various forms of new media. We had started a podcast in 2005 before Apple even added it to iTunes, and we were linking up with other people doing the same thing. We had an idea to start up a Catholic New Media Conference that would bring together Catholic bloggers and Catholic podcasters. We’d gather people from various television and radio outlets, along with those from newspapers, magazines, and blogs, all together for the first time: old and new media meeting together to discuss the future and collaborative opportunities in Catholic media.

I took on the entire onus of the thing myself. My oldest sister, Nancy, and our good friend Maria Johnson helped with some of the logistics. But for the most part, I decided I was going to do all of the prep work leading to the event myself.

This was stupid.

It was pride, perhaps, or an irrational need to control all elements of the event. I needed to make sure everything went exactly as planned, but I trusted hardly anyone but myself to make it happen.

When I now think back on my lack of delegation and trying to do everything on my own, it was one of the worst decisions I ever made.

I created all of the signs, graphics, and websites. I managed all of the scheduling. I planned all the talks and workshops. I developed all the contracts for the speakers. I even made their plane reservations. I stuffed the goody bags and put them on the chairs. I signed up all the sponsors. I even designed the name tags for attendees. I did countless media interviews to persuade people to attend. I planned to emcee the conference and deliver two different talks. I sprinted at a dizzying pace for weeks and months on end. I even coordinated the creation of a video game which was revealed during the event.

It was ridiculous.

In the midst of the chaotic planning, my buddy Moose generously allowed me to take occupancy in his local coffee house. I’d appropriate a table in the back and surround myself with papers and plans and contracts scattered around my computer as I drank from an ever-present coffee cup. I sat at the same table every day, working on my computer, making phone calls, and plugging away at the overwhelming details of this conference.

Then one morning as I began planning out my day, I realized that even though I could see on my calendar all of the phone calls, appointments, and meetings I apparently had conducted over the previous twenty-four hours, I had no actual memory of the day before.

Nothing.

I’m not just talking about an inability to remember what I had for dinner the night before or what I’d watched on television.

I had no memories from the day before as if the day before had never even happened.

I couldn’t remember waking up, where I’d gone, or who I’d seen or spoken to. I couldn’t remember if I’d done any of the things on my pages-long to-do list or anything I’d accomplished throughout the day. I couldn’t remember anything.

It was terrifying, like sinking into a black hole.

My mind was a completely blank space as if everything had been erased.

Inevitably, I thought about Great Aunt Lil.

I remembered her repeated postcards that one summer, and her missing memory of writing the card she’d sent the day before, or the day before that.

For a few moments, I literally thought I was having a stroke.

Fear swept over me, that inkling of childhood knowledge that Alzheimer’s is hereditary. Had it landed on me? I wasn’t even forty at the time. Was that even possible at that young of an age?

I did the next wisest thing I could possibly do.

I Googled “early onset Alzheimer’s.”

Dr. Google assured me that, yes, indeed, I did indeed have early-onset Alzheimer’s (and perhaps a fatal brain tumor, acne, and a stroke as well).

But as I pored through all the information that may or may not have applied directly to me, I discovered numerous and more relevant studies documenting the correlation between stress and other health problems.

Stress can worsen or increase the risk of conditions such as obesity, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, lupus, depression, gastrointestinal problems, and asthma, to mention only a few. In short, stress — so very prevalent in our twenty-first-century society — can make you sick.

A Harris Poll done on behalf of the American Psychological Association claimed that 64 percent of adults in 2014 reported that financial worries were a significant source of stress, ranking higher than other major sources of stress. In 2022, as we’re facing down the barrel of another recession or depression (depending on what the media spouts at us each day), I imagine that number is currently far, far worse.

In that same study, work was 60 percent; family responsibilities 47 percent; health concerns 46 percent.

But those were just the tip of the iceberg.

We are all stressed. We’re living in a world that wants us to be stressed. The world constantly provides new technology, new distractions, new commitments, and new worries to stress us out even more. If you’re not stressed out enough, let me send you another notification on your phone (of course, I’m sure you want to keep getting notifications whenever I publish a post here, so don’t worry about that).

Is that not enough? Here’s another social network to keep up with, along with a newsletter solicitation that you don’t remember signing up for (again…um…I’m not talking about this newsletter, though).

What exactly causes stress?

Again, looking to Dr. Google, stress can be caused simply by being sick (having dealt with a terrible bout of Covid and long-Covid after that, I can attest to this), by moving (which I’ve done more times in my life than I can recall without counting on my fingers and toes), change in marital status, a new baby, teenagers, children moving out of the house, a new job or unemployment, a death in the family, other family stresses such as an ill parent or child, emotional problems like grief or guilt, and more and more.

By the time I had gotten through the multitude of self-diagnosis lists online, I wasn’t as worried about Alzheimer’s anymore as I was about stress and my extreme lack of peace in my daily living.

In some strange way, it seems that even the idea of giving something up can cause additional stress. Imagine giving up checking email for a week, or not looking at social media for a month. How does that make you feel at this very moment? Maybe the mere idea of doing without something — for instance, not watching television tonight or giving up some other beloved thing — causes you a bit of consternation and stress.

In a world of 24-hour news cycles, of constant buzzing and beeping and notifications from our phones and watches and computers, of uncertain futures in an unstable economy while our own bank accounts may sit depleted and fruitless, of watching family and friends amble purposelessly through life while we ourselves may struggle to find our own sense of purpose, the idea of peace may feel perpetually elusive.

I’m not talking about world peace and an end to war, though that would of course be welcomed and wonderful. The peace we should seek is the peace that allows us to sleep more soundly at night, to be more joyful from one day to the next, and to go comfortably through each moment without worrying (as much) about the next.

There’s no cure-all to avoiding all stress or illness or brokenness or difficulties in life, but as we seek peace, as we try to manufacture some semblance of peace in moments of unrest, it may feel as attainable as trying to grab hold of water as it pours through our fingertips and into the drain below.

Often in our efforts to achieve peace, we inadvertently create more unrest, dissatisfaction, frustration, and more anxiety as peace slips further and further away.

Yet we chase after peace more fervently, often by seeking things that provide only momentary bursts of happiness: getaway vacations, expensive dinners out, binge-watching Netflix, pints of Ben and Jerry’s (though my temptation is Graeter’s Black Raspberry Chocolate Chip), overindulging in food, drink, or worse, seeking our base wants while inadvertently ignoring what we truly need.

We may fall prey to erroneous thinking that if we can correct situations in life — if we can just find the right spouse, the right job, the right house, the right thing — then we’ll have peace. If we could just fix that one problem, have that one thing — then we’d have peace.

Ironically, in my life, time and again, I have experienced the greatest levels of stress and pain when I take drastic measures to seek peace.

Conversely, my greatest levels of peace actually come when I deliberately stop taking drastic measures and instead learn to surrender to my current circumstances.

Surrender.

But isn’t “surrendering” giving up?

Exactly.

But isn’t “giving up” akin to failure?

Not at all.

To learn to surrender is the crux of self-mastery and self-discipline, and it’s a vital key to true freedom in our lives.

Rather than running away from fear, we surrender ourselves to the fact that we will at times be afraid.

Rather than seeking distractions, we surrender ourselves to whatever it is that is causing us the discomfort that keeps us from focusing.

It is not a matter of doing violence to ourselves but of controlling our passions so they don’t control us. It is often when we allow our passions and desires to take root and rule our hearts that we experience the most unrest and lack of peace.

Self-mastery — found in surrender — allows us to experience true human freedom.

And this freedom — true freedom — is what brings us true peace.

We often lose peace when we lose control of our passions, when we allow our lives to get out of balance with worry or self-medication or overwork, or a myriad of other paths that take us away from doing the right thing.

When we govern ourselves and our passions and our wants and desires, that’s when we have truly lasting peace.

If you are experiencing a lack of peace in life right now, if you feel tied in knots, don’t expect that finding peace will happen all at once. Don’t expect it to come from achieving some specific goal.

Finding peace comes as we take incremental steps toward learning how to have peace in all situations, even ones that normally cause stress.

Think of it this way:

Try to recall a time in your life when you had a seemingly insurmountable task placed before you that would require huge amounts of energy (mental or physical), focus, stamina, or other resources. Perhaps you were challenged to run a 5K or even a marathon. Maybe you set about to write a novel or rebuild a car engine. Maybe you once strove to make the dean’s list for several consecutive terms in school. Whatever it may be, there’s probably a time in your life when you had a goal that at first seemed huge.

But step by step you eventually reached that goal.

Forget about any other failures you may have experienced in life.

For a moment, just recall and hold onto a moment when you actually experienced great success.

How did you feel in that moment as you wrote “The End” at the end of a book, ran that point-two of the 26.2 miles of a marathon, or whatever that big accomplishment was for you? How did it feel to be successful?

You didn’t get there all at once but in incremental steps.

The diligence you put into the overall, long-term effort most likely yielded happiness, but you probably also felt deep contentment, a satisfaction that all of the sacrifices you had to make to get to that moment were all worth it.

In fact, you could probably say that it was self-discipline because you controlled your desire to goof off or do something else, which allowed you to reach that place of extreme satisfaction and contentment, and peace.

This is why when we control what we eat, get enough sleep, and strive for regular exercise we simply feel better. It is in mastering our appetites and fostering discipline, in reining in our desires for things that may not be good for us, and in simply focusing on what is right, that we experience the right peace.

When we experience freedom from our passions and from the seemingly endless need to chase after “more, bigger, and better” things in life, we find greater clarity in our daily lives. This makes it possible for us to direct our actions not only toward greater freedom and greater peace, but greater goodness in our own lives and the lives of others. When we’re at peace — when we learn to be at peace and correctly seek peace in all circumstances — we’re more capable of expressing love to others, of being better friends, of showing greater compassion and generosity. When we’re at peace, we’re happier with ourselves, more content to be who we were made to be as individuals, and more likely to express that individuality with confidence and joy. When we are free from the things in life that keep us captive, we can turn to seek more good in the world and in the lives of others.

Going back to that situation years ago when I was planning that conference and literally thought I was losing my mind, it’s easy in this non-stop world to get swept away in the chaos. I didn’t have early-onset Alzheimer’s or any of the other scary diseases I found online. Instead, I was a victim of self-induced stress, of focusing on the wrong things, of not being willing to let the right things go, of not seeking peace but instead embracing the chaos.

Since that time, I’ve spent years seeking ways to have more peace in my life. I haven’t always been successful (as my wife, friends, and family can attest), and even today my battle against lack of peace and severe unrest is a daily challenge. But my life is more purposeful and more meaningful and more peaceful than it was all those years before.

Surrender has made that happen. Incremental steps have made that happen.

Note: If this looked somewhat familiar to you, then congratulations. You must be one of the tens of people who read the book I wrote a few years ago, Tied in Knots: Finding Peace in Today’s World.

I admit: I cheated a bit this week.

I’ve been working on a more extended essay that needs more percolating time. So instead, I decided to share part of this slightly rewritten version of the first chapter of that book, the creation, and publication of which has a story of its own that perhaps I’ll share one day. Long story short: a couple of years ago I didn’t have peace over my relationship with the publisher and re-obtained full rights to this book again. I surrendered book sales and the spotlight because I believe many of the ideas in this book could help more people in different ways - such as sharing this chapter with you here. I’ve considered a major rewrite and self-publishing a second expanded edition. Time will tell.

One Last Thing: A Poem

Here’s something I haven’t yet shared via Greg Takes a Risk — poetry.

I was looking for something on my computer and came across a stack of poems I wrote a year or so ago. This one would have been appropriate to share a few weeks ago with my Unseen Frequencies post. That post, by the way, got picked up by several websites and really resonated with a lot of folks, particularly those who have dealt with traumas of various sorts.

If you’re one of the many new readers this week, I encourage you to check out that essay. You can find it here.

Once you’ve read it, come back and read this poem:

Fall 86

There was solace in M*A*S*H reruns.

Just before Christmas,

a new city,

a new school,

a million new people,

and not one to call a friend.

So on a 19-inch TV

my father won in a raffle,

I tuned the VHF

to the two episodes each day

to strangers, I knew

who were happy to spend time with me

promptly at 5.

Fr. Mulcahy and Hunnicutt and Hawkeye.

It wasn’t my favorite show,

but it was familiar enough,

when all else,

and everyone else,

was foreign

in that new city

that new school.

The beginning of aloneness

just before Christmas.